The tintype was an early Victorian photographic process which enjoyed huge popularity in the United States of America after its introduction in the late 1850s but it never achieved the same acceptance in Great Britain. Excited by other new experimental visual practices, the British photographic establishment quickly rejected the process and ignored its commercial applications, with one individual describing it as having “such a bilious tint” and being “unworthy of the present times”.1 Even in the 20th century, these small, dark images made on iron plates were derided as “these hideous, cheap-looking pictures”2 by eminent historians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim and this dismissal within British photographic history has continued to this day.

-

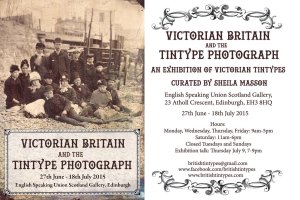

Agricultural worker with horse-drawn wooden cart

Unidentified photographer

Date unknown

¼ plate tintype

Sheila Masson Collection

The pose and subject matter of this image suggest that this man was particularly proud of his large draught horse and cart. Furthermore, ¼ plate tintypes were relatively uncommon and would have been more expensive than the typical 1/6th plates sold in Britain. Note the crazing of the collodion surface across the plate and the bubbling and rusting around the outside perimeter.

At 160 years since its invention, there are still no major publications written exclusively about the British tintype, although there are numerous titles discussing their American cousins. Even books focussing on historic photography at the British seaside typically ignore them 3 despite their considerable connection. Similarly British tintypes are typically infrequently exhibited except as side notes to other techniques. In contrast, in 2008 the International Center of Photography in New York staged a dedicated exhibition entitled America and the Tintype which featured several hundred examples from both the Permanent Collection of the I.C.P. and from private collections. Further more, the International Museum of Photography and Film at George Eastman House in Rochester, NY, currently includes a prominent display of tintypes in its history of photography gallery, directly adjacent to an American daguerreotype and also a calotype by D.O. Hill and Robert Adamson who formed the first Scottish photographic studio.

There has been a continual denigration of the tintype in the history of British photography which was inherited from the Victorians and which persists today. Despite this, the tintype has social and photographic significance in Britain which deserves greater consideration and acknowledgement. Happily I may now note that the 2015 “Photography: A Victorian Sensation” exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh has a large selection of tintypes on display, both from the Bernard Howarth-Loomes collection and on loan from the National Media Museum in Bradford. The exhibition “Victorian Britain and Tintype Photograph” and accompanying book (in the works) are part of an endeavour to establish the British tintype as a legitimate (if small) player in British photographic history.